By Matthew Engel

It is now possible – a mere 205 years after the original proposal for a Channel Tunnel – to travel overland from London to a foreign capital, i.e. Brussels, in less than two hours. But Belgium no longer feels like just another country, it feels increasingly like another planet.This isn’t routine journalistic hyperbole. The inhabited areas of Planet Earth are organised into nation-states – big, small; rich, poor; free, tyrannical – but nation-states all the same. Belgium is the first of them to begin mutating into something different. Generations of idealists, reformers and peace campaigners might feel delighted and vindicated.

At least until they start looking more closely.

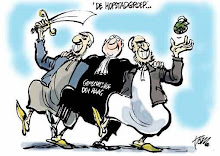

In the second half of 2007, when the Belgians were unable to agree on a government, there was speculation that the country would follow Czechoslovakia and split in two – into Dutch-speaking Flanders and French-speaking Wallonia. More knowledgeable observers said it wouldn’t happen because Francophone Brussels would be marooned inside Flanders, and it was impossible to resolve that contradiction.

Since then, the political crisis has eased slightly. Just before Christmas, the caretaker government was replaced by an interim version, which is supposedly more capable of decision-making. A fully functioning government is due to emerge by March 23. Maybe.

In the meantime nothing much can be done.

[...]

It is even harder to fathom that the apparent winner of the 2007 election, Yves Leterme, is still serving as the deputy of the man he beat, Guy Verhofstadt, and seems relaxed about it, too.

And the country appears to function well enough: to start with, the trains run on time, which puts Belgium way ahead of Britain.

But this is because Belgium has reached the point where the national government has ceased to matter. Over the years, the power has either been devolved downwards, to the regions and the communes, or passed upwards, to the European Union.

Belgium doesn’t feel the need to invade anyone else (“We seek a modest profile,” as one minister put it). And the crucial development has been the introduction of the euro. If Belgium still had its own currency, political instability might have been disastrous. Now that it doesn’t, the state can wither away. Shock revelation: Marx was right after all.

The country’s raison d’etre was always a bit flimsy. It was founded in 1831 because the people shared Catholicism and a dislike of being ruled from Holland. The European powers-that-were let it happen because they didn’t want any of their rivals ruling such a vital piece of geography.

Over the years, as religion faded, the disparate parts of the country began to share little more than their currency, their king and their football team. Now the currency has gone, the king is more marginal, and the football team is useless.

But underneath the place is seething. The two sides hate each other but carry on like a long-married couple, filled with mutual loathing, but too inert to sell the house and divide the CD collection.

And the chasm keeps growing wider. Wallonia, once rich, dominant and heavily industrialised, now has some of the most run-down cities in western Europe. The old coal and steel city of Charleroi could – with a few minor adjustments – serve as a film set for a gritty drama on late communism.

Flanders, meanwhile, has the same quiet, small, business-led prosperity as Holland. The contrast between Charleroi and, say, Antwerp is staggering, both economically and linguistically. An Anglophone has no trouble in Antwerp, once a French-speaking city. But I’ve seen a look of hate come into an old lady’s eye when asked for directions in French.

It’s risky even to whisper “raison d’etre”.

Belgian amity never recovered from the first world war when (in one version) French-speaking officers refused to speak the Flemish peasants’ language and sent them, uncomprehending, to their doom, and (in the other version) the Flemings were inclined to collaboration with the Boche.

As the years pass, the hate gets stronger, and the Flemings – in particular – more uncompromising.

I arrived to a chilling headline in one French-language newspaper: “Francophones, vous n’avez pas compris”. I thought this was a quote from a right-wing extremist. It came from Karel de Gucht, the foreign minister, the man in charge of the “modest profile”.

Outsiders don’t understand either. They think Belgium is boring but amiable. Yet it is only habit and temperament that stops it turning into Europe’s Middle East.

Published: February 23 2008

Source: Financial Times.

No comments:

Post a Comment